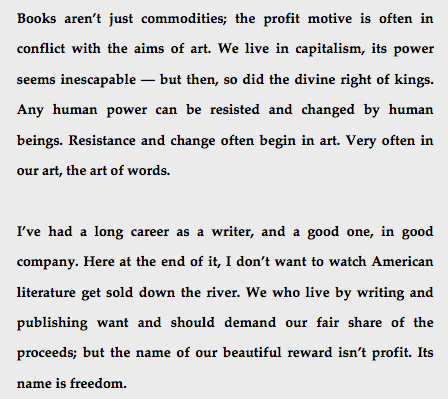

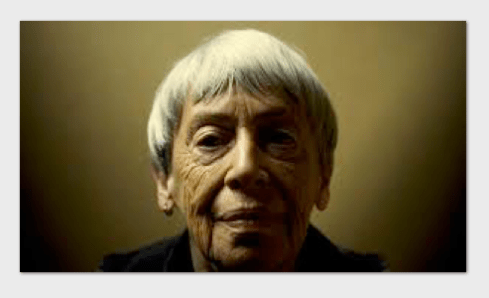

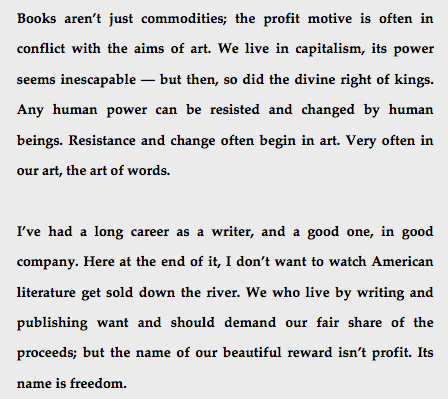

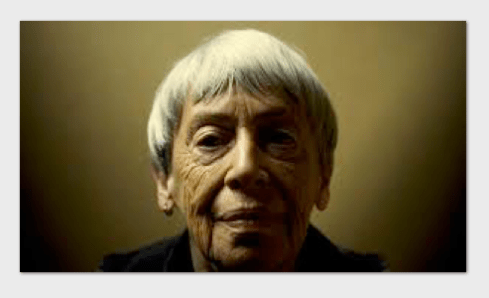

We lament the silencing, in this world at least, of that infinitely playful and protean voice named Ursula Le Guin. From her A Few Words to a Young Writer:

From her 2014 acceptance speech at the National Book Foundation:

˜˜˜˜˜

We lament the silencing, in this world at least, of that infinitely playful and protean voice named Ursula Le Guin. From her A Few Words to a Young Writer:

From her 2014 acceptance speech at the National Book Foundation:

˜˜˜˜˜

Since the very early navigations of DP, we have underscored the deep connection between the violence inflicted upon “food animals” and core human identity. Now comes Paul Tritschler with an analysis of killing floor psychology. The entire essay is worth a close read; excerpts below, with images added by DP, depicting various gradations of intensity in the transformation of sentient life into industrial meat.

˜˜˜˜˜

Animals may well have some sort of psychic antennae, some mysterious means to transcend the known substance of this world, but it seems more likely that their hysteria on the approach to the slaughterhouse has its source in the stench of entrails and in the distress calls of fellow creatures being mutilated and dismembered a short distance away. The notion of a profound death instinct at once masks this reality and assuages guilt: it allows people to acknowledge a discrete form of animal suffering, and at the same time to dissociate from the animal’s dreadful ordeal – in short, it shifts the responsibility for suffering from humans to the animal itself. Viewed from this perspective, the problem is not our desire to consume animals, but their desire to live.

5-10 HEADS PER HOUR WITHOUT DEHIDING MACHINE

The idea of a death instinct on the part of inferior life forms, otherwise referred to as food animals, is reminiscent of the mindset prevalent among many psychiatrists in the mid-nineteenth century – men such as Doctor Samuel Cartwright, who observed the outbreak of a curious condition among black slaves: the impulse to be free. Having dreamed up a diagnosis (dubbed ‘drapetomania’), for this mental illness – an illness with clinical characteristics that included a persistent longing for freedom, mounting unhappiness, or even occasional sulkiness – Cartwright concocted a cure: pain. He recommended the afflicted slave be whipped until their back was raw, followed soon after by the application into the wounds of a chemical irritant to intensify the agony. It brought the desired result: this mental shackling didn’t cure the condition, but it helped control the outbreak, greatly reducing the compulsion on the part of slaves to break away from their masters.

15-20 HEADS PER HOUR WITH DEHIDING MACHINE

As revealed by researchers such as Gail Eisnitz, a similar sort of logic prevails in slaughterhouses, where clubs or hammers are used to break the legs or spine of frantic animals in order to settle them down, and where cries of agony are addressed by cutting the animal’s vocal chords – especially when they get caught in the gate and are forced, fully conscious, to have their legs or head sawn off to speed up the line. And speed-up is very much the character of the slaughterhouse today, as increased efforts are made to meet the wholly unrealistic and unnecessary rise in global demand for meat – a rise that is monstrously resource intensive, environmentally damaging, and a major contributor to climate change.

30-40 HEADS PER HOUR WITH DEHIDING MACHINE

If not for reasons based on personal health, ethics or simply disgust, evidence suggests that becoming vegan is one of the most immediate and effective ways for an individual to reduce harmful emissions that affect climate change. Research by Peter Scarborough at the University of Oxford found that switching to a vegan diet – depending on the choices made for meat substitution – was a more realistic option for most people as a way of reducing carbon emissions than attempts at reduction within the areas of travel, such as driving or flying. The vegan diet, according to the research, cut the food-related carbon footprints by 60 per cent, saving the equivalent of 1.5 tonnes of carbon dioxide a year.

40-60 CARCASSES PER HOUR WITH DOUBLE MOTORIZED CHAINS

Animal slaughter has an adverse impact on the climate, the quality of life in society, and our identity. The extent to which we are willing to accept animal exploitation, and to tolerate animal cruelty – increasingly the key feature of the industrially-paced slaughterhouse today – bears some influence on how we see ourselves and others. At a number of points along the continuum, for example, there are clear indications that animal cruelty is a predictor of human violence and crime. The dangers in this regard were raised in Counterpunch Magazine by the investigative health journalist, Martha Rosenberg, who found that criminologists and law enforcement officials were at last beginning to acknowledge what the anthropologist, Margaret Mead, declared back in 1964: “One of the most dangerous things that can happen to a child is to kill or torture an animal and get away with it.”

˜˜˜˜˜

During the last week of 2017, The Guardian reported dramatic increases in plastic production capacity and investment, despite various international agreements that purport to diminish the plastic pollution that inevitably finds itself into the world’s oceans, already under tremendous stress.

Carroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environmental Law, stated: “We could be locking in decades of expanded plastics production at precisely the time the world is realising we should use far less of it. Around 99% of the feedstock for plastics is fossil fuels, so we are looking at the same companies, like Exxon and Shell, that have helped create the climate crisis. There is a deep and pervasive relationship between oil and gas companies and plastics.”

Greenpeace senior ocean campaigns director Louise Edge adds: “We are already producing more disposable plastic than we can deal with, more in the last decade than in the entire twentieth century, and millions of tonnes of it are ending up in our oceans.”

With this mind, we turn to artist-beachcomber Sheila Rogers and her powerful 2014 exhibit Oceans of Plastic.

˜˜˜˜˜

We recall words from Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, posing a question that cuts through the senseless blither of human monomania like a razor blade through a jellyfish:

˜˜˜˜˜

We begin our 2018 navigations with Wendell Berry’s Manifesto from the Mad Farmer Liberation Front, first published in 1973, and reappearing many times since for the simple reason that every word still has a loud ring of truth to it. Images are from the studio of Canadian artist Janna Watson.

NO SWEETNESS IN MY NERVES, JUST LIME JUICE

EVERYTHING I LOVE IS RISKY

˜˜˜˜˜

A glance back at 2017, and then onwards into the fog…..

2018

As in 2016, we close our 2017 navigations with a few words that bear repeating, offered by composer John Luther Adams in his 2003 essay, Global Warming and Art. Emphasis in bold added by DP.

˜˜˜˜˜˜

What does global climate change mean for art? What is the value of art in a world on the verge of melting?

An Orkney Island fiddler once observed: “Art must be of use.” By counterpoint, John Cage said: “Only what one person alone understands helps all of us.”

Is art an esoteric luxury? Do the dreams and visions of art still matter?

An artist lives between two worlds – the world we inhabit and the world we imagine. Like surgeons or teachers, carpenters or truck drivers, artists are both workers and citizens. As citizens, we can vote. We can write letters to our elected officials and to the editors of our newspapers. We can speak out. We can run for office. We can march in demonstrations. We can pray.

Ultimately though, the best thing artists can do is to create art: to compose, to paint, to write, to dance, to sing. Art is our first obligation to ourselves and our children, to our communities and our world. Art is our work. An essential part of that work is to see new visions and to give voice to new truths.

IN A WORLD ON THE VERGE OF MELTING

Art is not self-indulgence. It is not an aesthetic or an intellectual pursuit. Art is a spiritual aspiration and discipline. It is an act of faith. In the midst of the darkness that seems to be descending all around us, art is a vital testament to the best qualities of the human spirit. As it has throughout history, art expresses our belief that there will be a future for humanity. It gives voice and substance to hope. Our courage for the present and our hope for the future lie in that place in the human spirit that finds solace and renewal in art.

Art embraces beauty. But beauty is not the object of art, it’s merely a by-product. The object of art is truth. That which is true is that which is whole. In a time when human consciousness has become dangerously fragmented, art helps us recover wholeness. In a world devoted to material wealth, art connects us to the qualitative and the immaterial. In a world addicted to consumption and power, art celebrates emptiness and surrender. In a world accelerating to greater and greater speed, art reminds us of the timeless.

In the presence of war, terrorism and looming environmental disaster, artists can no longer afford the facile games of post-modernist irony. We may choose to speak directly to world events or we may work at some distance removed from them. But whatever our subject, whatever our medium, artists must commit ourselves to the discipline of art with the depth of our being. To be worthy of a life’s devotion, art must be our best gift to a troubled world.

˜˜˜˜˜

And finally, a link to Adams’ composition, Under the Ice:

Onwards to 2018……

As plutocracy gradually transitions into the full-blown tyrannical kleptocracy which Trump both signifies and embodies, we have been reflecting on an essay by Hannah Arendt written in 1964, shortly after her witnessing of the Eichmann trial. Images are from a 2014 installation by Wilfried Gerstel.

˜˜˜˜˜

NOBODY HAS THE RIGHT TO OBEY

˜˜˜˜˜˜

While politicians obey their corporate masters and cheat future generations through the sale of oil, mining and other rights within public lands and national monuments, we turn to Eileen Crist and her brilliant illumination of the heavy price we pay when we think of the natural world as a “resource” to be used by humans, excerpted from a longer essay.

Images are from the exquisite portfolio “Endangered”, by master photographer Tim Flach.

LICHEN

POLAR BEAR TRACKS

This week we lament the death of William Gass, though his writings will surely bubble and boil through the thickening karst of American literary culture for many years to come. To our ears (for he is at his most vivid when read aloud), Gass ranks as one of our truly great essayists, even when writing fiction. Fearless, vexing, elusive, partisan and polyphonous; an artist giving voice to the multitudes that swim – and sometimes drown – within the self. Below, two of these voices, the first from On Being Blue (1975) :

And second, from his richly mined essay on the challenges of autobiography, dating from 1994:

WILLIAM GASS: HONEST EXCAVATOR OF THE SELF

˜˜˜˜˜

Finally, a blue salute from book artist Morgan Lennox Whitehead:

˜˜˜˜˜